|

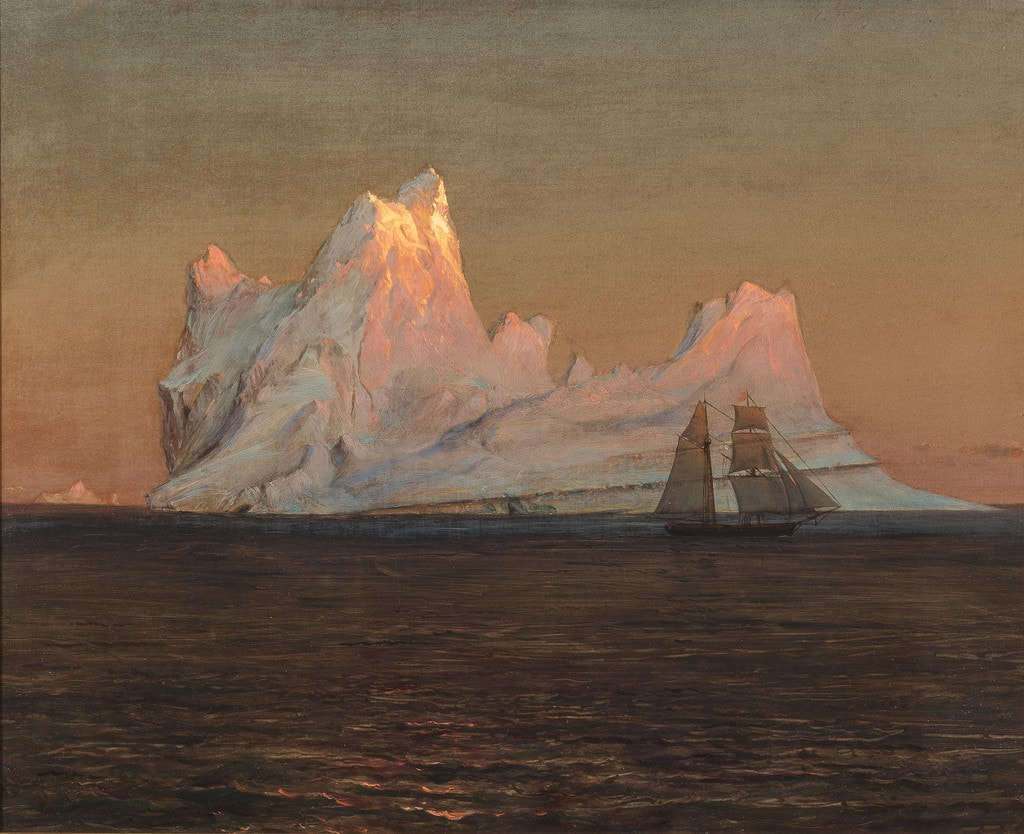

Ice doesn't last long anywhere on Earth, even ice that is older than humanity The Iceberg, Frederic Edwin Church, 1875 Sometime in 2017, a team of scientists plunged a drill into the ancient blue ice in a region of Antarctica known as the Allan Hills and pulled out a core that was more than 13 times older than the human race.

Ice does not last long anywhere on Earth, not even in the cold, dark heart of the miles-thick monoliths covering the Antarctic continent. Over millions of years these vast frozen oceans flow over the peaks and canyons of the land far below them. The heat from the bedrock melts the oldest ice at the bottom and winds strip away the newest at the top. When those scientists pulled that core sample, it was 1.7 million years older than any other they had found on the planet to date. The ice caps are melting is probably not a sentiment that fills you with dread. It feels too familiar, too inert to inspire a reaction. Ice melts. But next time you see one of those headlines, I want you to think about this particular piece of ice. Every empire that shifted the tides of history has lasted just a fragment of its existence. It is older than industry, than civilization, than art, than religion, than war, perhaps even than human thought itself. Before there was that ice cube, there was nothing of us. There is a rift between time as we understand it and time as it exists for that piece of ice. Our experience renders the latter inaccessible, alien. If human time is like is the octopus that might end up on your dinner plate on one of the the Greek Islands, geologic time is not just a bigger octopus but Cthulhu, a force beyond human reckoning. It’s something we can only begin to reckon with through inadequate metaphors about, say, tentacled sea creatures. The task, however — of trying to understand it — is as old as our species. That is, in part, what names are for. * In Iceland about 10% of the country is covered by glaciers. These glaciers are fixtures in the lives of the people there. They are a part of their towns and their culture. Their meltwater feeds their rivers, farms, and wells. Occasionally the volcanoes they conceal melt them from the inside, erupting in sudden glacial floods known as jökulhlaup. They have carved much of the island’s spectacular landscapes and they attract the tourists who are the lifeblood of Iceland’s economy . The glaciers there all have these beautifully direct names. Eyjafjallajökull, for example, translates to "glacier of the mountains of the islands” which is exactly what it is. The largest, Vatnajökull, or “glacier of the lakes,” is known for the subglacial lakes created by volcanic activity. Langjökull or “long glacier,” is 50km long but less than 20km wide. Like all good names these ones are both a reflection of the objects they describe and of the people describing them. They’re austere, but they also invest these glaciers with a personality; they make them characters of the landscape. When you begin to think of glaciers this way, it makes sense then that the people would mourn their loss as a kind of death. In 2014, when the glacier Okjökull melted to a point that it could no longer be called a glacier, the locals created a memorial. There’s a plaque and everything. “‘Ok' is the first glacier to lose its status as a glacier,” it says. “In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path.” A film crew made a documentary about the loss. “This is not a tale of spectacular, collapsing ice,” they say. “Instead, it is a little film about a small glacier on a low mountain — a mountain who has been observing humans for a long time and has a few things to say to us.” * I work at an advertising agency whose clients are mostly homebuilders. When they're getting ready to build a new community, they come to us to give it a name. These names tend to be remarkably anodyne, basically a container for boilerplate messaging and lifestyle imagery conveying how great it would be to live there. They don’t usually provide much information about what we’re naming. It’s sort of beside the point anyways. They seem to prefer names like “Grand River Heights” regardless of topography, grandeur, or proximity to a river. A couple years ago, I remember seeing a headline about a piece of ice twice the size of Chicago that broke off the Antarctic’s Brunt Ice Shelf. Two months later, another piece of ice half the size of Puerto Rico broke away from the Ronne Ice Shelf. These icebergs were named A74 and A76, respectively. To me, those names are perfect. The bland taxonomy is at once ideally suited to and at memorably at odds with the blank majesty of these sublime frozen continents consigned to oblivion. The letter represents the region where the iceberg originated and the number represents the order in which it broke away. When they break into smaller pieces, they get simple addenda: A74 becomes A74a, A74b, and so on. We use similar naming conventions for stars, another set of innumerable and otherworldly objects labelled with a modesty and utility that properly reflects our relationship with them. These names also help bridge the gap between something beyond our realm of experience and something within it. Icebergs can be just as immense as glaciers and ice contained in them may be just as old. But in the moment they break away, time shifts. Geologic time becomes human time. The ice becomes a mere object. Whether that object is the size of a tractor or the size of Belgium (as the largest iceberg in history was reputed to be), whether it’s in a few days or several decades, it will eventually be gone. We do not mourn these objects. These names reveal what the names of Icelandic glaciers obscure: that ice melts. * Barry Lopez is a writer who has been compared to Melville among documentarians of the natural world. In one chapter of Arctic Dreams, his masterpiece, he describes setting out by ship from Montreal into the waters north of Labrador bound for the Northwest Passage. He was following the journey taken by famous explorers like Frobisher and Baffin. “I had come to see the ice that silenced them all,” he writes. "The first icebergs we had seen just north of the straight of Belle Isle, listing and guttered by the ocean, seemed immensely sad, exhausted by some unknown calamity … Farther north, they began to seem like stragglers, fallen behind an army, drifting self-absorbed in the water, bleak and immense. It was as if they had been borne down from a world of myth, some Götterdämmerung of noise and catastrophe, fallen pieces of the moon. Farther to the north, they stood on their journeys with greater strength. They were monolithic. Their walls — towering and abrupt — suggested Potala Palace at Lhasa in Tibet, a mountainous architecture of ascetic contemplation.” Lopez is not subtle about the fact that his experience of these objects borders on the holy; that when he saw them it was as though he had been waiting quietly for a very long time “as if for an audience with the Dalai Lama.” Which makes sense. Like religious experiences, they brush up against the outer limits of our understanding: their dimensions in space and time, hidden from us; their elegant features in a perpetual state of change, carved and erased by the constant movement of the sea. Even seeing them, they rarely appear as they are. They play tricks on the eye as they peak over the horizon from great distances, the variegated hues of the sun trapped and dancing in their crystalline structures. We cannot know them, and that is why I think we will have lost something when they are gone. Comments are closed.

|

Past Essays |