|

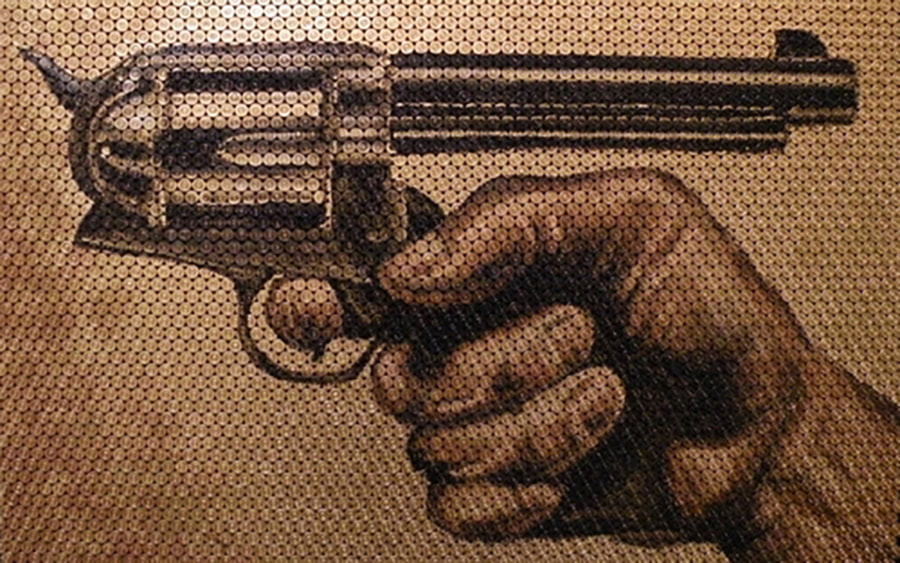

Guns are scary, which is why I can't understand why so many people aren't scared of them The atmosphere at a gun range is never not tense. If you’re a seasoned “operator,” to use the parlance of gun people, you are in all likelihood strictly intolerant of any nonsense of any kind because you respect these tools of death. If you’re a novice, you quickly learn why these people are this way. You don’t even have to shoot the gun. You just have to be near one when it goes off and you immediately understand why everyone’s balls are in their throat. And if you have any sense, yours are there too.

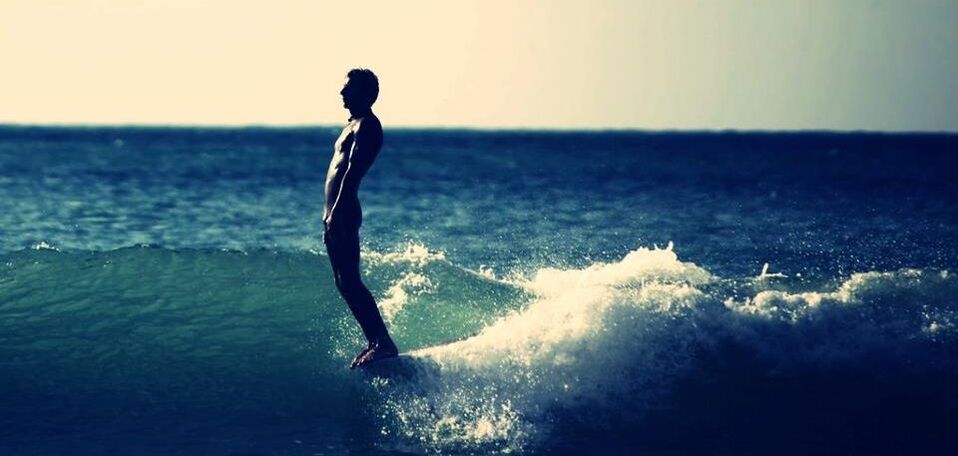

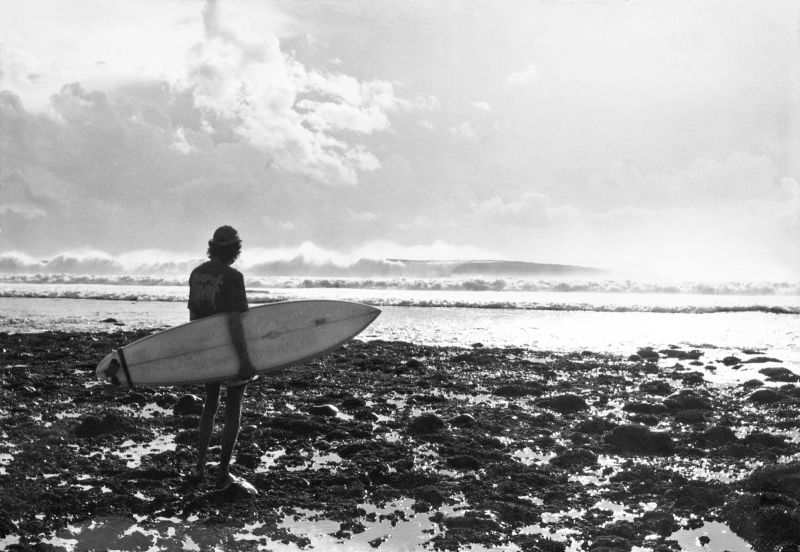

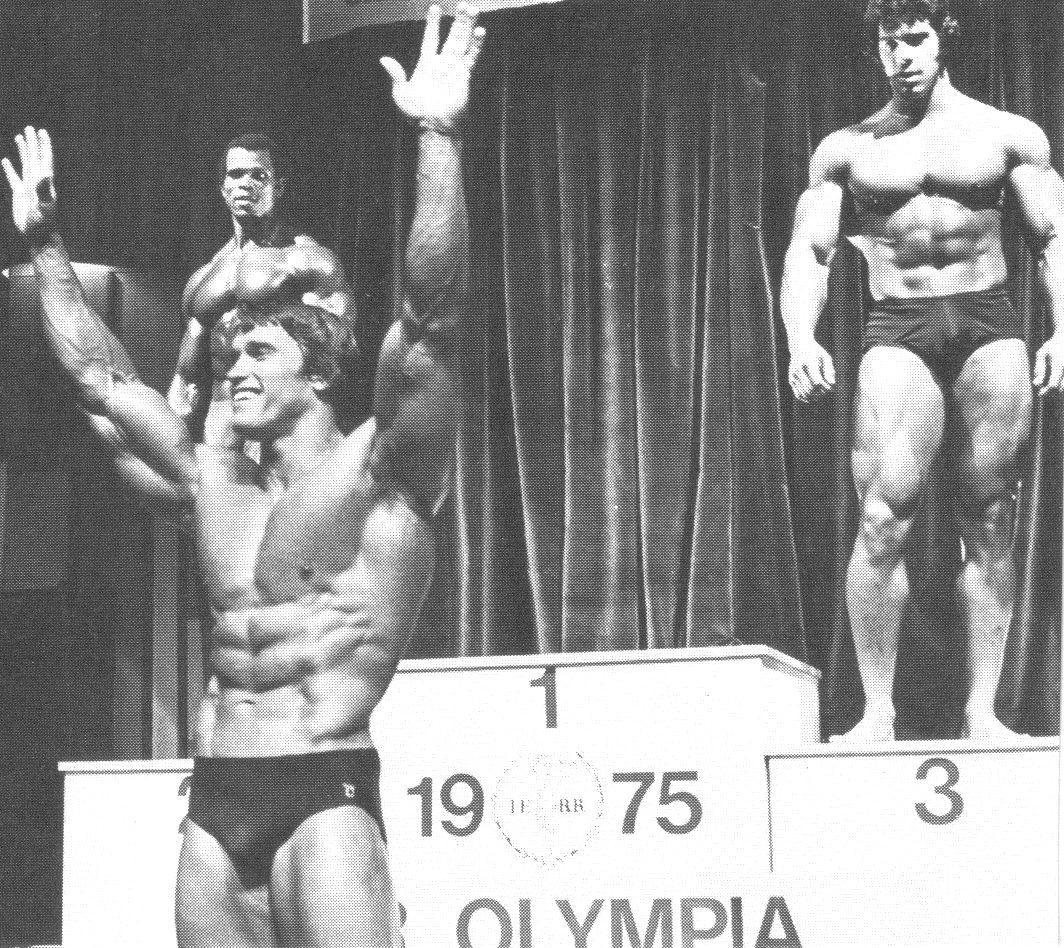

Recently, I went to a gun range north of Toronto, and there were a few things that surprised me. I remember, for example, that you could hear the sounds of the shots over the car engine as you drove down the street towards the range—something that might not be remarkable except this was an indoor range. The sound gets progressively sphincter-tightening as you get closer. The front shop is separated from the actual range by double soundproofed doors, at least one of which must remain closed at all times, otherwise the customers would be at constant risk of a burst eardrum. Ear gear on the range is a given, but the instructors also wear face masks, because the lead gets in the air and becomes poisonous after a while. When you’re shooting the instructors stand right behind you. They load and ready the gun and offer stern reminders if the barrel begins to wander anywhere that is not the target. The shells that are ejected from gun with each shot are scorching hot and have been known, on occasion, to fall down a shirt or, horrifically, behind one’s eyeglasses. They told us at the outset that whatever pain or injury this might cause, we are not to panic. The absolute last thing we should do is to forget about the gun in our hand. Before we got to shooting we were all escorted into a classroom where they explained all this, and shared a few other unsettling facts. Like for example, on the pistols, the firing mechanism claps back towards the shooter at about 1,000 feet per second. This mechanism passes just centimetres above the pin meant to protect your hand, and if your hand is in the wrong place, it’s not pretty. The instructors demonstrated this on these polyurethane models which were sitting on these tables at the front of the room. Before the instructors arrived, none of us touched them. Except one guy. This guy was, as I later overheard the instructors calling him, “a cowboy” but he might be better known to you or me as “an idiot.” He came in to the classroom and, in front of a room of total strangers, picked up the model gun and began pretend-firing it, like a kid who just saw Scarface. He—a grown man—did this totally unprompted. Once we actually got on the range, he quickly volunteered to shoot one of the pistols first, which he picked up, barely-aimed and shot like a video-game carjacker, and that was when the instructor decided his day at the range was over. He wasn’t allowed to touch another gun after that. Anyways, the point of all this is that these things (the guns) were intimidating. There was never a moment when we felt truly comfortable, and we knew that anyone who did was doing something wrong. For me personally, it took all of my focus just to stop my hands from shaking as I squeezed the trigger. And I’ve fired guns before. * People talk about guns being “fun” which I understand but also think is kind of fucked up. Their value as a toy is in direct proportion to the facility with which they can end a life. A shotgun or a rifle is more fun to shoot than a pistol, but it’s not as much fun to shoot as a grenade launcher. The ironic part is that the thing that makes it fun is also, typically, what makes us feel safe. You feel better when you have a bigger gun, even if it’s only as a deterrent for people with smaller guns. You see how this works: Maybe you get into guns because they’re fun, but eventually you feel like you need that gun, and you’re willing to allow for the possibility that lots of other people who probably shouldn’t have guns will have guns so you can have yours. You see, so you can protect yourself from them. If you’re American (they’re usually American) you’ll defend your right to have that gun by clinging dogmatically to constitutional documents; documents written by people who lived in a time when men earnestly challenged their rivals to duels, and for whom the term “heavy ammunition” meant a cannonball. It doesn’t matter whether you and your guns, however big, could actually defend yourself from a government intent on harming you (as the people who wrote those documents intended). The point is you feel vulnerable without them. And those stats about how you’re far more likely to harm yourself with your own gun than anyone else, well, that’s not you, is it… This is the problem with guns. It is also, as a way of thinking, so self-evidently misguided that I find it incredible it hasn’t occurred to every single person who has ever held a gun before. There are good reasons to have a gun, but keeping yourself safe is not one of them. Because guns are not safe. * My first time shooting was at a hunt camp about seven years ago, where my cousin was celebrating his 30th birthday. His father-in-law, Rocco, is a proficient hunter, and the protagonist of many entertaining stories. My personal favourite is the one about the porcupine who was eating his deck for weeks until one day, Rocco exacted terrible revenge in the bleary-eyed hours of the morning when, wearing nothing but boxer shorts and boots, he kicked open the front door and blew away the critter mid-meal. That weekend we went skeet shooting, target shooting, and hunting, and while I wasn’t supposed to be shooting any animals I was buttering up Rocco most of the weekend so he would let me. I didn’t actually want to kill something, it was more like I felt like I had to, to understand what it was like. I am (and you are too, probably) indirectly responsible for the deaths of many, many animals on a fairly regular basis, and I felt that doing the deed myself was a kind of moral obligation. Rocco told us about all the things that could go wrong with the gun before anyone shot anything. We were all appropriately on edge during the skeet shooting while some of us rookies tried to work the safety. At one point, Rocco told me about the older generation of Italian hunters who would walk using the gun as a bastone, the muzzle downward in the dirt like a walking stick, and how they didn’t seem particularly worried about the fact that a clogged muzzle increased the likelihood of blowing off the aiming part of your face. When we did finally go hunting, Rocco let me hold the gun as we walked, trusting I would be decisive and take the shot when something worth shooting came into view. After failing to take said shot several times, I started to get antsy. Then someone in our group pointed out something rustling in the tree directly behind us. Following Rocco’s prompt, I wheeled around and fired the shotgun into the branches overhead, killing what I didn’t realize at the time, was a bird. To say I “shot” the bird wouldn’t really be accurate. As my cousin pointed out, I was probably close enough to kill it using the gun as a club, plus the bird, whose body was probably slightly larger than a man’s fist, appeared to catch the bulk of the buckshot. I picked up the tail, which appeared to be the only part still intact. The other parts were scattered metres apart on the forest floor and camouflaged by the leaves and dirt sticking to the blood. I remember feeling nauseous and guilty, but more importantly I felt kind of shocked. My expectations about what a gun can do didn’t match what I saw it do. We’ve all seen it in movies: The bang, the smoking barrel, the person dropped by the force of the shot. But that’s not real, and I don’t think there’s anything that can prepare you for what those pieces of lead exiting that muzzle can do to flesh. My experiences since haven’t convinced me I would have been any more prepared if my target happened to be bigger or farther away than that bird was. That’s why killing something fucking devastated me. It was so easy, and the damage the gun inflicted was inversely related to how easy it was. Walking back to the camp, my mind ran through all the scenarios in all the darker universes of the things this gun could do to me or my compatriots with very little action from the person holding it. Killing that bird didn’t make me feel in powerful or in control or whatever. Instead it created this sense of dread—that, despite the safety precautions, we were always dangerously close to losing control. * Here is the way some doctors describe the effect that bullets have on the human body, as told to the New York Times after the school shooting in Parkland, Florida: “Bones are exploded, soft tissue is absolutely destroyed…bystanders are traumatized just seeing the victims”; “the exit wounds can be a foot wide…I’ve seen people with entire quadrants of their abdomens destroyed.” One talked about a victim who had a tiny entry wound in the front of her leg where the bullet had entered. When she turned on her side, the physician saw that the entire back of her thigh was gone. Granted, these are descriptions of military-style rifles, whose bullets travel twice as fast as ordinary handguns, and whose shockwaves blow through the body leaving massive cavities in their wake. But the fact is most guns, with few exceptions, are designed to kill or maim whatever they are shot at. Bullets from handguns still pierce and rupture muscle, bone, and viscera. The difference between these and a military rifle is one of effectiveness, not of purpose. But you and I, Mr. Gun Person, can probably agree on most of this. We don’t differ in our opinion about how devastating bullets are. And, unless shooting things has made you cold and dead inside, you’d probably even agree that you never really get used to inflicting that kind of damage on a living thing. What we disagree on is how likely it is that you, as someone who frequently handles guns, will come into contact with a bullet. What we disagree on is whether these tools are inherently dangerous—that this danger exists apart from the person operating them. You respect the bullet, of course. No nonsense. But while you might be slightly nervous around gun rookies, and you might fear people with guns who mean you harm, you do not fear the machine itself. I think you should. The rodeo is violent but does that make it wrong? At a week-long festival that advertises itself as the greatest outdoor show on earth, the rodeo is the main event. There are other things at the Calgary Stampede too—possibly safe carnival rides, fried foods stuffed will other fried foods, games in which you spend $40 to win something worth $4, fireworks—but I think people are probably more interested to watch a 160-pound cowboy climb atop a 1800-pound animal. In any case I was. I don’t know very much about rodeo. Before I went for the first time last year I had a vague interest in bull riding but knew little more than a few random bits of trivia. Like for example, I heard that the rope the cowboy holds onto is fastened to the bull’s genitals. The harder the bull bucks, the harder the cowboy has to hang on which, in turn, tightens the rope, causing the bull greater discomfort so he bucks even harder. Makes sense right? Turns out this is a myth. My university roommate, who we’ll call Tuf (after Tuf Cooper, a real cowboy whose real name was spelled with a single “f”), had transferred to the city earlier in the year to work as a manager for a company that shall remain nameless. He offered to host. I got in late one night in the middle of the week at which point we headed straight to a pub around the corner from his apartment. We caught up on the basic stuff—his soon-to-be-ex but now-current girlfriend, the zoo that was the American presidential race—while the highlights from the day’s rodeo played in the background. “How do they get them to buck like that?” he asked, not really expecting an answer. I told him about the testicle rope so I could then tell him it was untrue and went on to explain the rules: The rider climbs atop a bull, which locked in a tiny enclosure, and lashes his hand to the bull such that the hand doesn’t always come out when he gets bucked off.[1] When the gate opens the rider has to stay on for at least eight seconds to be eligible for a score. Half the score is awarded based on how well he has ridden (posture, poise, etc.), the other half is based on how “rank” the bull gets. The harder he is to ride, the more points awarded. In the top tier of this sport, the bulls are bred to be nearly impossible to ride, and I have seen them do things that should be impossible for a creature of that size. There is no testicle rope or other cruel methods of man that can make these animals do what they do.[2] * I went to my first rodeo expecting to be emotionally shaken by what I saw. I thought it would be a sort of self-reckoning, motivated by the same forces that drove me—someone who can barely stomach the prospect of gutting a deer but gets unnaturally excited to eat it—to go hunting for the first time. I wasn’t about to go drinking for four days straight in a cowboy hat and more denim than any human being should ever wear at once without witnessing the games at the heart of the city-wide bacchanal. But I also knew that many people do not like the rodeo. Even the description of several events sound inhumane. Calf-roping, for example, requires a cowboy to chase down a young calf on horseback, sling a rope around its neck while it’s still at a dead sprint, and then slam it into the ground to tie its four legs together. Steer wrestling is similar except the cowboy jumps off a moving horse onto the young bull’s horns and twists it into the ground (see photo supra). The chuckwagon events, which are basically modern chariot races, are also famously dangerous though not as objectively bothersome to watch as the other two. But I saw all of these things and, to be totally honest, they didn’t trouble me the way I thought they would. I became sort of obsessed with trying to understand why. * On day of the rodeo the rain was coming down hard and cold—like a bone-deep cold, which was particularly upsetting because it was July. We asked someone assembling hamburgers at a deserted stretch of food stands whether there was any chance the rodeo might get cancelled today. She said she doubted it. “Cowboys are tough,” she said. “What about the animals?” I asked. “That’s the only reason they might. If it’s too slippery for them to run, they could break their legs. I don’t think it’s that bad though,” she said in complete earnestness while staring through a curtain of rain. Tuf tried to light about three cigarettes under his poncho which was tucked up under his cowboy hat. Each one was sopping wet by the time he fished his lighter out of his pocket. But she was right, the events were not cancelled. So we sat shivering in the open-air stadium through the whole goddamn thing, clutching beers in our numb fingers like idiots. The show began with some lighthearted banter between the two commentators and the rodeo clown. Then the calf roping started. The very first cowboy caught his calf less than five steps out of the gate, dismounted, dropped the animal in the mud and tied him up, all less than six seconds. It was, in complete sincerity, one of the most impressive athletic displays I’ve ever seen. After a few seconds in the mud, the calf was untied and it popped up and trotted off to the gate on the far side of the arena. Even when the cowboys struggled, twisting the calves into all manner of unnatural positions, the animals always seemed to react the same way. That is, they didn’t react very much at all. They were smaller than the cowboys, but they were hardy little fuckers and they seemed fully capable of withstanding even the clumsiest attempts to pull them down. * One of the primary arguments against these events is that you’d never choke slam a kitten or sling a rope around a puppy’s neck[3] so why on earth would you do it to a baby bull? This is a dumb thing to say. Setting aside the physical differences, rodeo animals occupy a totally different space in our cultural imagination. If the day ever comes when a butcher in this part of the world can sell kitten chops without parades of people hitting the street with placards and megaphones, we can revisit this argument. Still, I understand that my personal feelings after attending a single day of rodeo is not necessarily the best barometer of the ethical implications of these activities. Between 1986 and 2012 nearly 90 animals have died at the Calgary Stampede, mostly as a direct result of injuries sustained during the chuckwagon and the steer/calf events. And there are thousands of rodeos that happen regularly throughout the Americas. I also think the anti-rodeo crowd—many members of which have been all too eager to rush to the defense of rodeo animals, using cuddlier pets as rhetorical stand-ins—does deserve some credit. It’s because of them that many basic animal safety regulations are now enforced at sanctioned rodeos. All this to say: I understand the inclination to want to protect these innocent[4] animals. I understand the events they are put through are violent and dangerous. The question I’m interested in here is whether something that is violent and dangerous is necessarily bad and ought to be stamped out of existence. I think that’s a more complicated question. * Tuf and I have been friends for over a decade. We went to high school together, played football together, roomed together through all four years in university. I remember one year, at a Halloween party, I challenged a person dressed like a wrestler to a wrestling match in the living room only to find out that his costume was actually a uniform, and that he was a regionally ranked amateur. Following that beating, Tuf wanted a piece of the action, and in the ensuing tussle I was hit in the face until I bled all over the living room. Inconsiderate though it was to our host—a former-friend who, as far as I know, never forgave us for ruining her carpet—we agreed it was one of the best parties we ever went to. Ordinarily, Tuf and I go out of our way to avoid confrontations with strangers (good-sporting wrestlers at parties excluded). And yet between us, even well into our adult years, there’s always been a rather vicious sense of competitiveness. We always get into these fights with one another, friendly and yet, in a lot of ways, not. I don’t have that relationship with anyone else and I don’t think I could. There’s an unspoken understanding that whatever reason or injury, these bouts end with a beer and a cigarette. It’s a primal way to measure and affirm our sense of ourselves. To put it another way: the violence is something I cherish. I think Tuf does too. I know this sounds like some macho psychobabble but you don’t exactly have to be Freud to see that this sort of thing: a) happens all the time, particularly in sports, and b) usually underscores a rather strong relationship. It is also, I think, the closest most of us will ever personally ever come to understanding the relationship between a cowboy and a rodeo animal. There are a few key differences. One of the easy ones is that the animals can’t consent (refer to FN 4 for all I’m going to say on this). The other is that stakes are much higher. People and animals do die at the rodeo, but I also think that heightened risk generates a heightened form of respect—love, even. It is not a simple business transaction, where the animal is bred, fed, and turned loose. They have personalities,[5] professional records, people whose job it is to stroke their flanks while they eat wheat. Even the humble calf is not just some prop to be used in the show. There’s a reason “cowboys love their animals” has become a cliché. The rodeo is an evolution of ranching practices; it remains a way of life in which humans rely on their animals and their continued well-being. To forget that seems to demonstrate a willful ignorance of the spirit of the event. * Most of our stereotypes of cowboys portray them as tough, laconic, and even-handed. They have a steel grip on their values. They’re independent, apprehensive of strangers, polite, and fiercely loyal. These people—and by extension, their animals—are not to be fucked with. I met a few people like this in Calgary. One of them was an older gentleman who castigated Tuf for flicking his cigarette on the cobblestone street, getting up from his huevos rancheros on a nearby patio to explain that that, buddy, is how forest fires start. Another was a police officer in a truck who—clearly sensing we were hungover—encouraged us to “get it in ya” while we were slurping Gatorades at a crosswalk. Another was a very bored bouncer me and Tuf were talking to about hockey and politics one night in what seemed to be the one of the few empty parts of town. Tuf has long been in the habit of calling kind and good-hearted individuals “good people.” That bouncer was good people. Earlier that night we had met up with our friend’s mom, who was also in town for the Stampede. She was good people. But then Tuf said that by way of comparison my mom—who was sometimes known to be a little abrasive and mean—was not good people. I did not accept this. I told him my mother was one of the goodest people I knew and, basically, where the hell does he get off making that kind of deep and cutting judgment about her? He shrugged it off. Neither of us talked about it after that, but it brought out a strange contrast between us and the people I had come to associate with the culture here. It seemed totally obvious that someone like the bouncer, or the police officer in the truck, or even the old man talking about the forest fires would never make a passing judgment like that about someone who was not from here. They would not question their character or something they held dear. We who were not from here did that sort of thing all the time. We do it to stake out that moral high-ground. And when I was writing this, I thought about that a lot, and all the judgments I would inevitably pass. --- Notes: [1] This usually results in but one of a variety of truly difficult-to-watch injuries that bull riders suffer. [2] For a case study, I give you the bull quite appropriately known as Air Time. [3] Leashes are not the same thing… [4] Though I do think that “innocence” and “consent” and similar concepts invoked to defend animals end up being inapplicable here. Rodeo animals are no more or less innocent than bull that seems hell-bent on goring you, or a wild steer that succumbs to sickness and hungry coyotes out in the prairies. They’re no more or less capable of consenting than some free-range beef that was raised with the utmost tenderness before it was painlessly slaughtered. These concepts are projections, useful only insofar as they make us feel guilty or gracious. [5] My favourite example is Bodacious, the bull who to this day is viewed as the most dangerous in rodeo. He had a reputation for the way he bucked, where he would force the cowboy forward just as he whipped his head back. On one famous occasion he nearly killed a rider, crushing most of the bones in his face. Bodacious was never disqualified or retired because of this, and yet it was widely seen as a purposeful and malicious act, even though the perpetrator was an animal. You see, formidable as he was, in rodeo circles, Bodacious was an asshole. On the horrible, embarrassing, incredible experience of trying to surf I love surfing. Well, that’s not quite right. I love the idea of surfing. The exotic locations, the commitment to something so elemental, ephemeral, and violent: the wave. I recently finished reading Barbarian Days, a story about two young men who drag themselves malnourished and broke to the other side of the world to chase it. They would camp out by the sea and gnaw on rotting fruit rinds just to get in the water at sunrise. The truth is, I love surfing the way a sixth-grader loves the popular girl going into high school: with a combination of impossible longing and fear. And that uncomfortable crush has never been stronger than it was last summer, when I went to Hawaii for the first time with my family. * I don’t think I’m alone here. I’ll occasionally see photos of friends on vacation, crouched uncertainly atop a rental board or holding it underarm while they stand on the beach, looking wistfully out there. I get it. Thing is, I don’t think it’s possible to really convey what they’re feeling. In conversations (or an essay like this one) it’s very easy to come across like the guy who he caught a glimpse of the Virgin Mary in a piece of burnt toast. You might have and I’m sure it really was incredible, but I’m also having a tough time getting as excited about it as you are. This difference—between actually experiencing this thing and trying to tell your friends about it—sort of mirrors the dissonance between watching someone surf and acknowledging who is, at least occasionally, doing the surfing. The dude. The burnout. The artist. The wanderer.[1] The vocal fry sizzling, van-living, beachside-camping kid who’s going to get a real job soon he swears. For example, arguably the best surfer in the world right now is a 23-year-old named John John Florence[2] who is impossible to confuse with anyone other than a surfer. Bleach blonde hair, wiry frame. He’s sort of distractible in his interviews. Uses words like “gnarly.” He just came out with the world’s biggest budget surf film to date called View from a Blue Moon (for which I have watched the trailer well over a dozen times) and in that movie/trailer, he is another person entirely.[3] Seeing him stuck in a chair for an interview is about as comfortable as watching a sea turtle drag its big, stupid body across a beach, but watching him in the trailer is like the first time you realized that thing is actually made to swim. The difference isn’t just huge—it’s transformative. For me, on the other hand, getting in the water had precisely the inverse effect. Surfers have their own term for beginners: they’re called kooks. As surfers know, and as kooks quickly learn, we do not belong in the path of the great forces at work in the ocean. The wave inflicts levels of physical and psychological humiliation, and other surfers compound this humiliation to scare us off and keep us out. If you ascribe to the belief that this is more sacred art than sport, then we kooks are obnoxious tourists in a holy place. Which is to say, I’ve been a beginner at a lot of things, but never has it been quite as embarrassing as it was being a kook in Hawaii. * I had taken a surfing lesson once when I was in Mexico. We took a shuttle to a beachside hostel where we spent the first 10 minutes on the sand learning to pop up and down. That was the whole lesson. Just get from your belly to your feet as fast as you can. So when we got to Hawaii, there would be no lessons. All I wanted was a board and directions to a spot where I wouldn’t die. As soon as we got to our hotel on Waikiki beach I looked out through the open-air lobby and saw surfers in the water, bobbing like action figures way out at a distant break. Most had parked in this public lot up the side of the harbour where they launched off a rocky pier. Waves didn’t seem too intense. Maybe shoulder-high, I thought to myself. It’s just water for Christ’s sake. I went out over there alone for a closer look. In the parking lot, there were vans with surfboards lashed to the roof and pickups with surfboards sticking out of their cabs. A few people were tailgating, sitting on cement parking blocks and huddled around charcoal barbecues, their white flakes rising on currents of hot air. I walked out on the pier to where the surfers were going in and coming out of the water, stepping gingerly across the gaps in these immovable boulders while crabs scuttled over and around the slick contours. I saw a guy standing there with his surfboard under his arm, watching people who I imagined were his friends in the water. I asked him if he was going in. He said he was. I asked him if this was somewhere someone who hadn’t really surfed before could try and he said absolutely not. He was nice about it, but I got the feeling I had violated some social norm, like asking a stranger to puff on their cigarette. He said I should walk farther down the beach. Here the reef was too shallow and when I fell I would get knocked around pretty good. I noticed he had an accent and asked where he was from. He said Israel. I asked whether or not he was enjoying his vacation and he told me (rather excitedly) that he actually lived on Oahu. After I walked back to the beach I saw him and the other surfers walking back across the pier, their silhouettes set against the sunset like something you’d see on a postcard. At that moment, nothing in the universe could dispel my impressions of how cool these people were. Over the next few days I saw him hanging around our hotel’s courtyard, working a booth where he sold wind mobiles. I never approached him again. * In the four days I was in Waikiki, the guy at the surf booth urged me not to go surfing because the conditions sucked. But this was Hawaii, and I wasn’t about to let some surf booth operator tell me I shouldn’t go surfing in Hawaii. Now I couldn’t say for sure whether that first outing was more a result of the shitty conditions or my overwhelming incompetence but I spent a solid hour paddling to spots where the waves just finished breaking (I would soon learn that this is very much a waiting game), trying to stand up on teeny waves that didn’t so much break as collapse into a mushy pile of whitewater, and confusing the shimmering reef under the clear water with what might have been a shark. I also learned what a rash guard is and why people wear them. So that sucked. But only a few days later, we flew to the island of Maui and we heard about a surf spot close to our apartment complex called Whaler’s Village. It’s an outdoor mall on the beach with a sandy break just a short walk away from some of the hotels. I rented a board from a hut on the beach, approaching the owner to ask about the conditions. He made a bunch of hand gestures and told me a bunch of things I pretended to understand. Then he handed over a big blue soft-top and I took off towards the water. * In Barbarian Days William Finnegan writes that once a wave exceeds 20 feet, the number of surfers who are willing to ride that wave drops off precipitously. He quotes one surfing scholar who puts the number ready to ride 25-foot waves at less than 1 in 20,000. “I had surfed alongside a few big-wave specialists on the North Shore, but I thought of them as mutants, mystics, pilgrims traveling another road from the rest of us, possibly made from a different raw material,” Finnegan writes. He quotes an old-time big-wave rider who once said “big waves are not measured in feet, but in increments of fear.” I saw in this passage a crucial revelation about surfing: fear is constant and there is a point when things get so heavy that talent doesn’t really matter. This—and this is not an exaggeration—kept me up at night. Comparing the waves here to anything over 20 feet was preposterous, of course, and yet knowing this was no more comforting than your father’s perfunctory reminder that you would be safe riding a gigantic-seeming roller coaster as a kid. I wasn’t scared of drowning, exactly. When I imagine drowning I imagine a struggle, but there would be no struggle here. In the lizardy part of my brain, it seemed half possible that my body would be swallowed and washed into non-existence. Worse, this feeling didn’t even really go away after the first day surfing in Maui. Even in bed, I could still feel in my limbs and my gut a faint sensation of being tossed around, like I was being shaken in the cradle of a giant’s massive palms. Oddly enough the only time this feeling went away was in the water. In the moments I turned my head to paddle, I didn’t have time to think about how big the wave was going to get before it came down on top of me. * Getting out there was probably the toughest part. The first few sets were were easy to paddle through, but as I got farther out, the roiling whitewater rushing towards shore became taller and too difficult to push over. So, I went under. Given that my board was probably buoyant enough to float a refrigerator (beginners all get these huge clumsy boards because they’re easier to ride) this was also a challenge. The first few times, I thought I would try to hold onto it, barrel-rolling under the water and hooking my hands and my heels over the rails. This was dumb. The force of the wave would rip the board away from me and send me tumbling back towards the shore. Trick was let go and dive deep, letting the rubber ankle leash hold on as it bounced through the waves. I did make it to the break where probably six or seven other surfers were waiting. I sat up on my board maneuvering by twirling my legs in the water like eggbeaters. The fact that many of these surfers were, by my estimation, ‘legit’ was actually comforting. I tried not to crowd them while acknowledging that where they were was probably the best place to wait. I stood up on a couple waves briefly but when I fell and came up I was battered repeatedly by the next sets (a phenomenon known as getting caught inside). Every time I tried to climb on my board, the next wave was right there to sweep the board right the fuck out from under me. The whole experience conjures the image of a drill sergeant, throwing buckets of water in your face while you gasp for air. The ocean might as well have been asking why I’m such a pussy. After about 30 minutes of this, I crawled ashore for a break. * After reading Finnegan’s book, I wondered for a long time whether or not I should write anything about surfing, mostly because I’ve been told it’s difficult-to-impossible to write about surfing well if you actually surf, let alone if you’re a goddamn tourist. In an essay-style review of Finnegan’s book for New York Magazine, Jay Kang writes about some of the cringeworthy first-person accounts of surfing in Hawaii: the long rides in to shore, the “ecstatic bliss,” the wipeouts (there are invariably more examples in this piece you’re reading, I’m just too green to know what they are). “(They) were writing about the sport in the way they might have written about eating ahi poke for the first time in a Hawaiian hotel,” Kang writes. The kicker was that this “kook bait,” as he calls it, was penned by Mark Twain and Jack London. Which brings us to the obvious question: what am I—a writer unfit to sharpen Mark Twain or Jack London’s pencil—trying to do here? The honest answer is that I don’t know. All the reasons I’ve run over in my head—to distance myself from this romanticized notion of surfing (“the sunbaked spiritual pornography,” as Kang calls it), to describe the not insignificant physical and psychological toll of actually doing something that seems so graceful--now sound stupid. I’m sure that as a landlocked Canadian, I’ll never learn to really surf, and despite my absolute best efforts, I don’t think I’ll ever be much better at writing about it. But you’ve made it this far so if you’ll indulge me for just a little while longer, I’ll try to tell you what it is like to stand up on a wave. * You begin paddling, hard, and long before you can judge whether you should be trying to catch this wave. Soon, your board will begin to tip forward as the water rises up behind you, but unlike the other times, the nose will not dig into the water. The wave will not pass under you. It will not curl overtop of you. It will begin to carry you. You’ll pop up, not really expecting to be able to stand but you’ll stand anyways. You will feel like you’re hovering above the water, like you are defying physics. You are not defying physics, though. That big dumb board could probably carry a second person, but this thought will never occur to you—not if you rode a thousand more waves like this. You’ll become lucid, piercingly aware that you are now doing exactly what you were trying to do since you got in the water—that the other times when you made it half this distance aren’t like this; not even close. You’ll remember something you saw when you were watching the other surfers and you begin pumping your legs to gain momentum. You are now slightly more surprised you haven’t fallen off but, like a bicycle gaining speed, your balance is more assured. Now the wave is beginning to die under your feet. You don’t just want to jump off. You want to stay in control. So you fall forward onto your board, bracing yourself with your arms. This is when you finally slide into the water. You climb back on, calmly. You paddle back towards the beach. But in your goofy reverie, you forget about the ocean behind you. The undertow pulls you into a breaking wave and smashes you hard into the steep sandbank. Your body is full of sand and shame. You’re suddenly very aware that the beach is pretty crowded and you scramble to pick yourself up. You see kids running with boogie boards straight into breaking waves, doing backflips as they shoot off the water like a ramp. You wonder if the people at the hut are going to check if your board is damaged. You think it is definitely damaged. It was incredible and ugly in equal parts. But you also know that when you leave this place, you will not regret having failed. --- Notes: [1] I actually got these from a list of surfing stereotypes that were published in a surf magazine. They are, of course, not exhaustive and I already feel bad about lumping massive numbers of talented surfers into these not-so-flattering categories. [2] Even just his name… [3] I know a lot of this has to do with things like production value, but I can’t imagine the effect is greatly diminished when you watch him surf in person. Edited Feb. 2024 The first time I read John Saward’s column for VICE, I remember laughing so hard I had to stop to catch my breath. Here’s the opening paragraph from his piece “Why I Love Watching Ron Jeremy Fuck”: To witness Ron Jeremy have intercourse is to witness a grizzly bear eat a flamingo, or an orphan try to break into a vending machine. He is a manifestation of the grotesque male id, jamming fingers and genitals into every orifice at every opportunity, doing all of these things simultaneously, not making sense, not following some plan, just a man bludgeoning the human body with his sexual impulses. It is like watching a chimpanzee try to open the package of an Xbox controller. Upon finishing my teary-eyed second reading, I dropped whatever it was I was supposed to be working on that day and read everything else he’d published. If you read VICE, you’ve likely come across something he’s written. He’s mostly known for his meditations on masculinity from his column “We Are Not Men” and, more recently, for his takedowns of various media/celebrity blowhards. Beyond sheer incisiveness and wit, the writing also has incredible heart. He wrote about pick up artists, which was simultaneously one of his funniest pieces and a somehow sympathetic appraisal of the deeper insecurities there. Last father’s day he wrote about his dad and on Valentine’s Day he wrote this. Easily my two favourite pieces, though, are about boxers. His piece on Mike Tyson is one of the best things VICE has ever published and his piece on Joe Frazier might be even better. After I read the Frazier piece I felt, for the first time, like I needed to tell the author how great I thought his stuff was. I emailed saying I wanted to be able to write like him and asked if we might be able to talk about his work, what he reads, etc. His response remains one of the most cherished emails I’ve ever received. You can read it in full below. In my early-twenties self-loathing had become a sort of recreational activity. I had just graduated from college and could not determine whether it was a period of growth or decay or stagnation. I suspect now that this is an affliction shared by many creative people (those who are immune to this are robots who need to be destroyed), but at that time I struggled to detach myself from it. I still wrote, but for purposes I could not identify. It was on the backs of receipts and in messages typed into my phone while riding the subway and on sprawling, unstructured Word documents. Writing was a messy, violent ejection of fractured ideas that I couldn’t assemble or refine. The bodybuilder as a tragic figure Near the end of the 1977 docudrama Pumping Iron there is scene where a few men—who to this day remain some of the most famous bodybuilders of all time—are gathered to celebrate the conclusion of the 1975 Mr. Olympia competition. Arnold Schwarzenegger, the de facto leader of the great bodybuilders is lying supine on a couch, smoking a little pot and wearing a t-shirt that says “Arnold is numero uno.” The other contestants are milling around the tiny room including a freshly defeated Lou Ferrigno. They’re eating fried chicken and—because it’s Lou’s 24th birthday—cake. Up until this point, the filmmakers had been showcasing the psychological warfare of the recently concluded spectacle, even taking some creative liberties to stage some of the more camera-friendly moments themselves. Throughout the movie, the steely and seemingly untouchable 5-time champ, Arnold, has been carefully working Lou, not so much softening his already fragile psyche as much as dismantling it. The final jab comes in that moment with Lou standing off to the side, as alone as a 6’4” 280-pound mountain of muscle can be in a room of that size. After a happy birthday song, led by the possibly stoned Austrian, the group starts chanting for a speech, unsympathetic to the fact that Lou—who’s been nearly deaf since childhood and is, in all likelihood, having a pretty shitty birthday—probably doesn’t much care to give one. Lou smiles: “I got nothing to say, I just want to eat my cake.” I love that scene and while it might be oversentimental to say it’s heartbreaking, it is surprisingly moving. It’s not tough to imagine it was scripted and used by the filmmakers to put the proverbial bow on everything they had been wrapping up to that point. If that’s true, it worked. Some might argue the events of the film culminate the moment the judges announce the results, but they’d be wrong. There is only one moment, and it’s when Lou utters those words. * While Pumping Iron, is, at it’s core, just a flick about gawking at fleshy statues, Lou and Arnold make it something more. Lou is denied the win, but he’s also denied any real closure, fading into the background amidst the celebration. This film is very clearly meant to be a comedy but if you reacted like I did to the cake-eating scene, it is also a tragedy. For the entire movie it seems obvious that Arnold is being set up to be the man who’ll win the Olympia. His journey to the title seems almost effortless, fated, and punctuated by laughs, photo-ops and various homoerotic frolicking with his gym buddies in the sun-kissed city of Venice Beach (he compares ‘the pump’ one gets from lifting to coming, enough said). Lou stands in sharp contrast, training in a dimly lit gym in Brooklyn with people who are definitely not bodybuilders, working—no, struggling, loudly, painfully—to build a body that will beat Arnold. In a follow-up documentary made years later, the filmmakers would describe the bigger and younger Lou as the dark prince that would threaten the golden king.

He finished third. What you may not have known about Lou is that, as a bodybuilder, he was paid next to nothing and worked as a sheet metal worker for $10 an hour until a friend cut his hand off. Lou left after that. His father, who is depicted in the film as his overbearing coach, was deployed as a character by the filmmakers and wasn’t nearly as involved in Lou’s training as he was made out to be. Even after Arnold retired from bodybuilding following that competition, Lou never won an Olympia. Yet, the film almost manages to convey all this—gesturing at it through darkened shots, laboured screams and futile resolve—without betraying its tone. In other words, you’re clearly meant to feel Lou’s pain but you’re also meant to root for Arnold. What’s jarring is the conclusion, the feeling that all is right while what is essentially a poetic injustice hovers just below the surface. Catharsis there is not. That may sound ridiculous since this film catapulted Lou into the acting role that would eventually define his career. Yet, when we take a step back to consider how the only real non-CGI’d human being to portray the Hulk made his way into the public eye, it’s not only ironic, it’s downright sad. He’s reduced to the kid standing in the corner, watching the others smoke pot and eat cake. He just wants to eat his cake, but in that moment they even manage to deny him that. |

Past Essays |