|

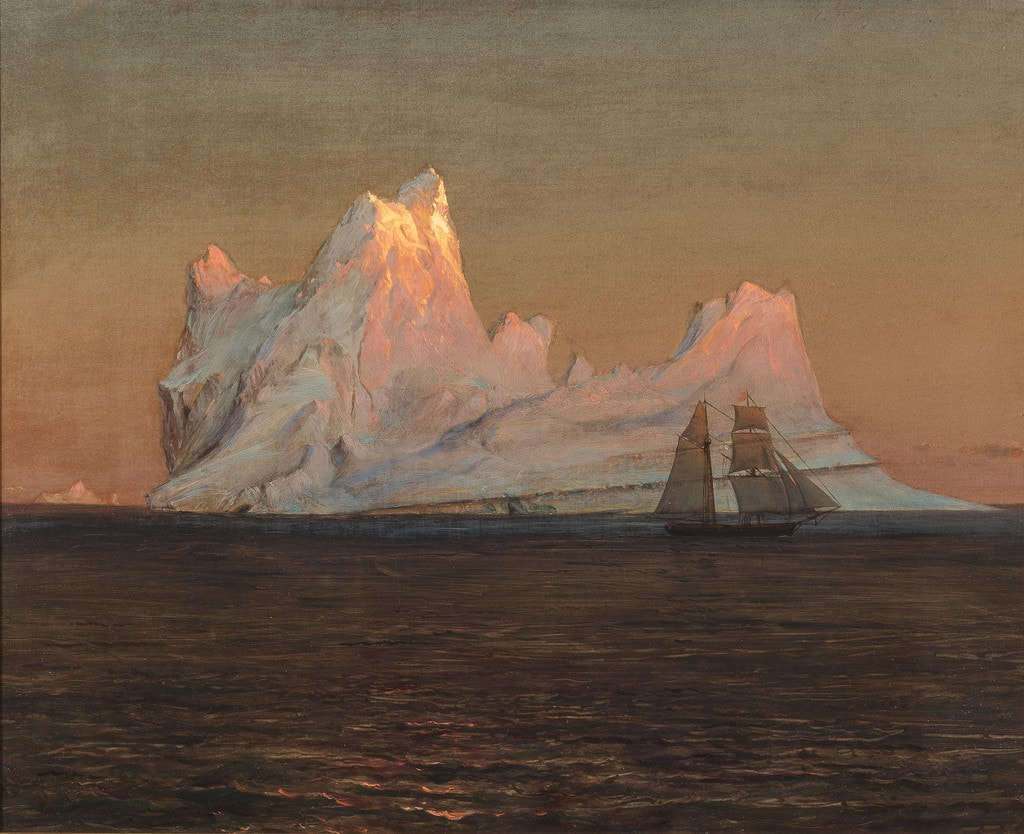

Ice doesn't last long anywhere on Earth, even ice that is older than humanity The Iceberg, Frederic Edwin Church, 1875 Sometime in 2017, a team of scientists plunged a drill into the ancient blue ice in a region of Antarctica known as the Allan Hills and pulled out a core that was more than 13 times older than the human race.

Ice does not last long anywhere on Earth, not even in the cold, dark heart of the miles-thick monoliths covering the Antarctic continent. Over millions of years these vast frozen oceans flow over the peaks and canyons of the land far below them. The heat from the bedrock melts the oldest ice at the bottom and winds strip away the newest at the top. When those scientists pulled that core sample, it was 1.7 million years older than any other they had found on the planet to date. The ice caps are melting is probably not a sentiment that fills you with dread. It feels too familiar, too inert to inspire a reaction. Ice melts. But next time you see one of those headlines, I want you to think about this particular piece of ice. Every empire that shifted the tides of history has lasted just a fragment of its existence. It is older than industry, than civilization, than art, than religion, than war, perhaps even than human thought itself. Before there was that ice cube, there was nothing of us. There is a rift between time as we understand it and time as it exists for that piece of ice. Our experience renders the latter inaccessible, alien. If human time is like is the octopus that might end up on your dinner plate on one of the the Greek Islands, geologic time is not just a bigger octopus but Cthulhu, a force beyond human reckoning. It’s something we can only begin to reckon with through inadequate metaphors about, say, tentacled sea creatures. The task, however — of trying to understand it — is as old as our species. That is, in part, what names are for. * In Iceland about 10% of the country is covered by glaciers. These glaciers are fixtures in the lives of the people there. They are a part of their towns and their culture. Their meltwater feeds their rivers, farms, and wells. Occasionally the volcanoes they conceal melt them from the inside, erupting in sudden glacial floods known as jökulhlaup. They have carved much of the island’s spectacular landscapes and they attract the tourists who are the lifeblood of Iceland’s economy . The glaciers there all have these beautifully direct names. Eyjafjallajökull, for example, translates to "glacier of the mountains of the islands” which is exactly what it is. The largest, Vatnajökull, or “glacier of the lakes,” is known for the subglacial lakes created by volcanic activity. Langjökull or “long glacier,” is 50km long but less than 20km wide. Like all good names these ones are both a reflection of the objects they describe and of the people describing them. They’re austere, but they also invest these glaciers with a personality; they make them characters of the landscape. When you begin to think of glaciers this way, it makes sense then that the people would mourn their loss as a kind of death. In 2014, when the glacier Okjökull melted to a point that it could no longer be called a glacier, the locals created a memorial. There’s a plaque and everything. “‘Ok' is the first glacier to lose its status as a glacier,” it says. “In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path.” A film crew made a documentary about the loss. “This is not a tale of spectacular, collapsing ice,” they say. “Instead, it is a little film about a small glacier on a low mountain — a mountain who has been observing humans for a long time and has a few things to say to us.” * I work at an advertising agency whose clients are mostly homebuilders. When they're getting ready to build a new community, they come to us to give it a name. These names tend to be remarkably anodyne, basically a container for boilerplate messaging and lifestyle imagery conveying how great it would be to live there. They don’t usually provide much information about what we’re naming. It’s sort of beside the point anyways. They seem to prefer names like “Grand River Heights” regardless of topography, grandeur, or proximity to a river. A couple years ago, I remember seeing a headline about a piece of ice twice the size of Chicago that broke off the Antarctic’s Brunt Ice Shelf. Two months later, another piece of ice half the size of Puerto Rico broke away from the Ronne Ice Shelf. These icebergs were named A74 and A76, respectively. To me, those names are perfect. The bland taxonomy is at once ideally suited to and at memorably at odds with the blank majesty of these sublime frozen continents consigned to oblivion. The letter represents the region where the iceberg originated and the number represents the order in which it broke away. When they break into smaller pieces, they get simple addenda: A74 becomes A74a, A74b, and so on. We use similar naming conventions for stars, another set of innumerable and otherworldly objects labelled with a modesty and utility that properly reflects our relationship with them. These names also help bridge the gap between something beyond our realm of experience and something within it. Icebergs can be just as immense as glaciers and ice contained in them may be just as old. But in the moment they break away, time shifts. Geologic time becomes human time. The ice becomes a mere object. Whether that object is the size of a tractor or the size of Belgium (as the largest iceberg in history was reputed to be), whether it’s in a few days or several decades, it will eventually be gone. We do not mourn these objects. These names reveal what the names of Icelandic glaciers obscure: that ice melts. * Barry Lopez is a writer who has been compared to Melville among documentarians of the natural world. In one chapter of Arctic Dreams, his masterpiece, he describes setting out by ship from Montreal into the waters north of Labrador bound for the Northwest Passage. He was following the journey taken by famous explorers like Frobisher and Baffin. “I had come to see the ice that silenced them all,” he writes. "The first icebergs we had seen just north of the straight of Belle Isle, listing and guttered by the ocean, seemed immensely sad, exhausted by some unknown calamity … Farther north, they began to seem like stragglers, fallen behind an army, drifting self-absorbed in the water, bleak and immense. It was as if they had been borne down from a world of myth, some Götterdämmerung of noise and catastrophe, fallen pieces of the moon. Farther to the north, they stood on their journeys with greater strength. They were monolithic. Their walls — towering and abrupt — suggested Potala Palace at Lhasa in Tibet, a mountainous architecture of ascetic contemplation.” Lopez is not subtle about the fact that his experience of these objects borders on the holy; that when he saw them it was as though he had been waiting quietly for a very long time “as if for an audience with the Dalai Lama.” Which makes sense. Like religious experiences, they brush up against the outer limits of our understanding: their dimensions in space and time, hidden from us; their elegant features in a perpetual state of change, carved and erased by the constant movement of the sea. Even seeing them, they rarely appear as they are. They play tricks on the eye as they peak over the horizon from great distances, the variegated hues of the sun trapped and dancing in their crystalline structures. We cannot know them, and that is why I think we will have lost something when they are gone. You may threaten the future of civilization, but I can’t seem to live without you In 2019 the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom was thinking about the things that might kill us.

In his vulnerable world hypothesis, Bostrom asks us to picture human creativity as the process of pulling marbles out of a giant urn. The white ones represent inventions or discoveries that enrich humanity. The grey ones are a mixed blessing; think nuclear fission which has given us nuclear power but also nuclear weapons. Bostrom says at some point we will pull a black marble from the urn, “a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it.” Since we’re still here Bostrom believes this hasn’t happened yet, but I’m not so sure. We may have drawn one back at the dawn of the industrial revolution and are only now coming to terms with the implications of our invention. For the first 150 or so years of its existence, this technological marvel was thought to be harmless. It became the lifeblood of our economies and energy systems. It heats our homes and fuels our way across land, air, and sea. Almost anything can be made from it. Discoveries cannot be undiscovered, so once any marble comes out of the urn it cannot go back in. This marble is different, though. Even if we could put it back, we probably wouldn’t. It is too good to give up. I. The Oil Defender’s Gambit Oil is an amazing substance. This has never been in dispute, yet it seems to be a point of confusion when we talk about our dependency on it. These conversations usually go something like this: I attend a rally against fossil fuels which, at the rate we are burning them, threaten to change our climate in the coming centuries in ways that imperil human civilization. I think this is bad. I would prefer civilization was not imperilled. A friend, or perhaps one of my enemies, later sees a few of my pictures from the rally and helpfully points out that people do not attend rallies to protest substances they think are amazing. He notes that the car I drove there runs on fossil fuels; the lid on the coffee I picked up beforehand is made with oil derivatives; the supply chain that brought that coffee to my local coffee purveyor is powered by oil. But why stop there? I might respond. That car I drove? You need oil to make the tires, the seats, and most of the vehicle itself before you put anything in the tank. The house I live in? The paint, the caulking, the shingles, the plumbing. Oil again. My clothes, the ones I wore to the rally probably, are woven from synthetics that wouldn’t exist without oil. My shoes, oil. The computer on which I’m typing this, the seat I’m sitting on, cold medicine, chewing gum, toothpaste, deodorant… Exactly! My interlocutor says. It is hypocritical to ask that we stop using oil when you yourself rely on it every day. Which, fair. Running water, computers, takeout coffee, shelter — all good things. If my convictions obligate me to give up not just the conveniences of modern life, but the clothes off my back and the roof over my head, I am a hypocrite. But the fact that I can’t stop contributing to the problem shouldn’t be taken as an indication that it’s not really a problem. That’s why it’s a problem. II. A Miracle of The Modern Age Maybe the modern world didn’t have to be this way. In the early 1900s, electric cars were considered superior to gasoline-powered ones. They were faster, more maneuverable, and more reliable. And besides, “you can’t get people to sit over an explosion,” one high-profile investor predicted confidently in 1896. Yet following the Second World War, when the U.S. factories manufacturing armaments went back to making civilian wares, a new exercise in nation building got underway. A few missteps by top electric car companies, cheap fuels, some clever marketing, and America’s burgeoning car culture became entirely gasoline powered. Strip malls, highways, suburbia, and huge swathes of modern infrastructure owe their existence to that culture. As one documentarian of the era noted, “Had this period of random technological mutation selected for the electric, the social history of America would be unrecognizable.” Then there are plastics, a fossil fuel byproduct. Did we have to make everything out of plastic? Probably not, but in the 1960s this novel material was regarded as a miracle. I don’t mean this in the colloquial sense. I mean plastic could do things that the laws of nature seemed not to permit. It didn’t break like glass. It was cheap, reproducible, and could be molded into virtually anything that would last basically forever. “The hierarchy of substances is abolished,” Roland Barthes writes in one essay. “A single one replaces them all.” Then there are oil’s applications for which there is no suitable substitute. There is no substance like jet fuel, nor will there be for the foreseeable future. The only way the average Canadian can experience the world outside of driving distance — Tokyo, Cape Town, Tangiers, Rome — is if we decide to keep running the vast machine that extracts the remains of primordial creatures from the earth and burns them. It’s impossible to imagine life without oil. It has shaped everything from our daily lives to the world’s cultures and macro systems in ways that transcend any individual’s understanding or moral judgment. Is oil bad? That’s like asking if technology is bad. Or the sea. It's too big to fit in the question. III. Oil’s Greatest Trick There are new omens that now demand our attention, mostly because of how easy they are to ignore. Plastics that won’t naturally degrade for centuries are swirling in ocean patches larger than the Maritimes. In a few decades, there’ll be more plastic in the ocean than fish. Nanoplastics are flowing through my blood stream and yours. We don’t know what that means for our health, exactly, but we know our bodies can’t process it. In your lifetime you’ll eat an estimated 44 pounds of the stuff. As Jeannette Cooperman darkly points out in one essay, you'd have an easier time digesting a seven-year-old. After one cross-Atlantic flight, my personal greenhouse gas emissions from this singular event exceed the annual total of the average resident of 56 countries. These tend to be countries that are uniquely vulnerable to increased storm severity, drought, flooding, crop failures, political unrest, civil conflict, and a whole host of interrelated issues that are exacerbated by the airline industry, our energy systems, and basically every other oil-powered system on which civilized life depends. You may think it’s an exaggeration to say climate change may lead to the collapse of civilization within the next few hundred years. Maybe it is. But consider: our dependence on oil is changing the climate faster than an extinction event in earth’s distant past that extinguished 95% of all animal life. That event might have taken as little as 100,000 years, the geological equivalent of the click of a camera shutter. And those are fucking rookie numbers compared to what we're doing now. A recent paper found that earth's wildlife populations have plunged nearly 70% on average in the last 50 years. We feel insulated from these forces but we are not. The end of civilization will come long before the end of human life, and there are many degrees of hardship and unpleasantness between the two that not even our most pessimistic prophets can fathom. Civilization is not a robust construct. Push hard enough in the right places and things begin breaking faster than they can be fixed. Yet, oil is so enchanting that it pushes these things to the mind’s peripheries. I want to find better ways to live without oil, but in the meantime, I have places to go and things to get done and I need oil to do almost all of them. There are dozens of factors that affect my choices, and concerns over the continued prosperity of civilization tend to get drowned out by the hum of the car engine or lost amid the excitement of a package just-arrived from a distant factory or disappear into the quiet anticipation at an airport gate. IV. A World Remade Could we have said no? Even if we could foresee our current predicament, could we forgo everything oil has made possible? If we had, the connections between our cities would likely look something like they did in the 18th century. Comforts, conveniences, and technologies beyond the imagining of history’s richest royals and aristocrats, now democratized, gone. The wealth of entire nations, left in the ground. We can’t even say no now. Saying no at the dawn of the industrial revolution might have seemed as foolish as continuing the course we’re on today. We often love things that are bad for us, but there are few vices that could be said to be essential. Maybe that's the honest appraisal we need to begin to remake the world without oil. I don’t know what that new world will look like or how to get there, but I’m certain that if we look far enough into the future, a world where we fail won’t look anything like ours today. Originally commissioned by BESIDE magazine, a which is great and visually stunning publication that you should read and support. Issue 13 is coming out soon. The Biden presidency does not guarantee a brighter future “I’m glad people are happy, and the pure stupid resplendence of their joy fills me with dread.” - Colin McGowan

Conspiracy theories used to be interesting. The moon landing and JFK assassination. Extraterrestrials and planes plucked out of the sky. They arose from gaping holes in our psyche. They were questions that demanded answers, or answers that raised deeper questions. They were products of obsessive puzzlement and fever dreams, like the first cavemen who invented god to explain the world. A lot of them were insane, some of them dangerous, almost all of them were wrong. But they were usually good stories. And in the quiet moments we needed good stories, even if the only answers they could give us were about ourselves. Conspiracy theories today are boring. They’re boring because they are prompted less by big questions than by answers we don’t like. The only ones that seem to matter still orbit around the venal desires of a former president who cannot imagine nor care to imagine a world beyond his TV. They aren’t even stories, really, but a perpetual loop of blunt, self-soothing fictions. COVID is a hoax because my life would be much easier if it wasn’t real. Climate change isn’t happening because those pencil neck scientists and sanctimonious activists irritate me. Donald Trump won the election because everyone who said he would lose is a liar. Peel away the ornate layers of conspiracy theories today and you’ll almost always find something like this at the centre: the irrepressible contrarian spirit of some of the dumbest motherfuckers alive.(1) Over 70 million people in the U.S. voted for Donald Trump. Many of them will never stop believing the election was stolen from him. They will retreat into their fictions, every half-baked “isn’t it convenient that…” and “don’t you think it’s strange that…” which disassemble our shared reality a little bit at a time. * I am happy that Joe Biden won the election. I wasn’t dancing in the streets or anything, but I believe he is sincere about not wanting to watch thousands more Americans die every day from a novel respiratory disease so that’s progress, I suppose. I also have problems with Joe Biden. Beyond the hair sniffing and encroaching senility, my biggest problem is that he’s vanilla, a flavour the relevant parties bet would taste like sweet delight to everyone who had been eating shit for four years. As a political tactic, it worked…sort of. He won the election, but the margin wasn’t exactly comfortable. Trump was so obviously monstrous they thought they could deliver a decisive victory by offering little beyond “I’m not him.” That this didn’t happen should surprise no-one, least of all the strategic wizards in the Democratic party. Which is irritating given how they’ve maligned the progressive wing of their party in the name of executing this grand middle-of-the-road vision. They accused progressives of being naïve for pushing agenda items like free healthcare and appropriate taxation for multi-billionaires, while the party brass remained steadfast in their commitment to “unity” with many of the morally rudderless goblins across the aisle. Conventional wisdom in this poison racket suggests that helping ordinary Americans avoid bankruptcy which too often accompanies, say, a cancer diagnosis just isn’t politically feasible. Doing too much to prevent humanity’s plausible extinction will cost too many jobs right now. In fact doing too much of anything too soon to address these and similar problems—problems that overwhelming numbers of citizens want addressed, like, now—is still somehow seen as beyond the scope of their work. A better world isn’t possible according to the people charged with making our world better. But maybe I am being too harsh. On his first day in office Biden signed several progressive executive actions, and has taken many similarly progressive actions since. Perhaps most significantly, he revoked the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline which would transport oil through America’s heartland between Alberta and Texas, a move that prompted a mealy mouthed statement from our own Justin Trudeau. Several coronavirus actions were simple and relatively easy but also hugely consequential; things like “come up with a response plan.” Biden even appears open to the prospect of forgiving student debt, a priority for progressives. For this, and many other moves, he deserves credit. But if you think all of this bodes well for the future, I’ll have to stop you right there. Because there is little evidence to suggest that Biden will keep this up if his progressive colleagues stop doing their job, which, at this point, seems to be throwing staplers at his head until he begins governing the way his base wants him to. One especially cynical take is that Biden will do for the progressive left what Donald Trump did for the evangelical right which is to neuter them as a political force. The “we’re on the same side” sentiment will force them to fall in line with a vision for the country they neither wanted nor accepted, the same way God fearing, hymnal signing southerners rallied behind a New Yorker who has a howling void in the part of the brain that might be said to house Christian values. Joe Biden is no more like Bernie Sanders than Donald Trump is like Mike Pence. The people Biden has chosen to staff his administration are, as you might imagine, much more like him than they are like the quickly growing progressive proportion of the electorate to whom, historically, they’ve just been saying no.(2) The problem with getting politicians to do their job is this: most of us subscribe to the belief that “politics” is a thing you do when you go vote. Real life is what you do before and after that. Trump invaded “real life” in such a way that even people who were not immediately affected by his policies couldn’t ignore him. But very few people felt they could do anything about it until the election. Noam Chomsky, a contemporary intellectual and political thinker, believes this attitude is misguided. In the lead up to the election, Chomsky was asked approximately 8 million times(3) who he would be voting for and without any hesitation or reluctance whatsoever he said Joe Biden and you should too. Biden’s campaign positions were, according to Chomsky, more progressive than any president’s in American history by a country mile and that is not because, in his words, Biden had some personal conversion. It’s because he had been getting hammered by progressives. “The left position has always been: You’re working all the time, and every once in a while there’s an event called an election,” he told Anand Giridharadas. “This should take you away from politics for 10 or 15 minutes.” After you vote it’s back to the real work of politics. Keep hammering. * Luke O’Neil, a very smart writer whose book you should buy, wrote about the phrase “history won’t look favourably on this.” He is not a fan. He says it’s a form of punting responsibility for current problems to the future when some hypothetical historian will arrive and offer a scathing appraisal of how badly we’ve screwed up. It’s also, he points out, not even true. History is written from the perspective of winners who have a way of conveniently omitting or positively reframing all the terrible things they’ve done. The thing is though, people don't always use this phrase in the predictive sense. It's an appeal to vanity. It’s used to get people to think about their legacy, to raise the spectre of an unforgiving judge and jury in hopes they’ll stop doing the bad things that'll land them in the courtroom; even if they are very likely to escape conviction anyway. We are lucky that Donald Trump was not only stupid but also frequently drawing attention to how stupid he was. If history is in fact unkind to him, this will be why. But here’s a little non-hypothetical: There absolutely will be leaders in the future riding the same waves that carried Donald Trump to the White House and some of them will be at least as charismatic and considerably less dumb. That’s going to be a problem. Trump’s presidency did not equip America to stop this from happening again. Just the opposite. It weakened many of the institutions that were meant to stop it in the first place. Joe Biden has lulled many people into a false sense of security. People seem to think Trump is an aberration of the U.S. political system rather than a logical extension of it. For that reason, far too many people are being far too kind to Joe Biden. They say that now is not the time(4) to be critical of his administration because of the mess he inherited. Or they’ll say what an incredible achievement it is that Kamala Harris is the first female minority VP, which is true right up to the point it's used to sweep aside every whiff of criticism as misogynistic or racist. These people will stop paying attention because the good guys are in office without understanding that, all else being equal, the “good guys” aren't invested in changing the stuff that needs to change. They are, after all, creatures of this system. * Trump-era conspiracy theories now influence political decisions in a way traditional conspiracy theories never have. Most people who stormed the Capitol at the former president's behest may have been dumb, but they were not the garden variety conspiracy theorists of yore. They were “regular” Americans. They were people with things to lose if they got caught planting pipe bombs or attempting to take law makers hostage. In some ways, they embody certain American values more than other Americans. After all, is it not very American to carry an antipathy and distrust of government so deep that you would refuse to marshal even a basic level of critical thinking when a time travelling informant tells you Democrats are sacrificing babies, and your messiah is a gilded-hair reality TV show host who has failed at every venture in his privileged life? It’s basically apple pie. And yet, and yet, the most dangerous thing about these conspiracies is not that a lot of people believe them, it's that they have now been insinuated into not-insane world views. Little pieces have wound their way into respectable conversation, not always explicitly, but you can see the fingerprints if you look closely. Smart and cynical people have recognized precisely how useful these fictions are. This includes politicians like Mitch McConnell who have allowed these fictions to flourish right up until the moment the rioters arrived very pissed off at their office doors. But it also includes people in your life. They’re the ones who’ll say “yeah obviously QAnon is outrageous” but who feel in their bones that it is not nearly as big a problem as the growing chorus of progressives demanding a better world from their governments. They're the ones we’ll have to convince that “no, $7/hour hasn’t been a livable minimum wage for years” and “no, the people who ask for more are not actively trying to destroy American businesses.” We’ll have to convince them that the medical establishment is not, in fact, conspiring to “shut down the economy” as part of some elitist power grab, but because keeping people healthy is a prerequisite for getting back to business as usual. We’ll have to convince them that the political action demanded by more than 30 years of dire scientific warnings on climate change is not a grand scheme to destroy our way of life, but to preserve it.(5) If you're looking for the seams where our shared reality is coming apart, this is it. We'll have to begin stitching it back together if we ever hope to eventually alleviate suffering that, right now, many of us refuse to see. -- Notes: (1) I wish I wasn't the kind of person who said things like this. There are people in my life who take this stuff seriously who I want to believe are kind-hearted and smart. But the people driving this movement are dishonest and dumb, and if you buy what they’re selling, that’s a dumb decision on your part. Also, you’re making the rest of us dumber by forcing us to explain why it’s dumb. What I’m saying is, I’m running out of excuses to make for you. (2) One of these appointments—Neera Tanden, whom Biden pegged to head up the largest office in his executive branch and someone who has gone to great lengths to discredit Bernie Sanders supporters as malicious political operatives because they said mean things to her online—might be read as an emphatic “fuck you” to progressives. (3) Chomsky, who has the demeanour of a kindly and incredibly sharp garden gnome, personally responds to many of the thousands of emails he receives on a regular basis and does way more interviews than anyone should be expected to do at age 92. (4) By which they mean “at no point ever in the future.” (5) This is not to suggest that our scientific or medical authorities are beyond reproach. Both have made serious mistakes during the pandemic. Climate science measures complex planetary systems over huge timelines and deals in vast ranges of probability. It’s reasonable to be skeptical. But skepticism is not what these people want. They believe scrutiny is unnecessary because these whole fields of study are corrupt or based on nonsense. A “hoax” does not require deeper investigation except as a means to dismiss it. An attempt to reverse engineer the world’s greatest boxer’s rise to the top of the world pound-for-pound rankings  Img. via ESPN Img. via ESPN First off, I should probably apologize for my headline. I don’t actually know what makes Vasyl Lomachenko, currently the best boxer in the world and one of the most fluid and graceful fighters to have ever lived, just that. In fact, I doubt anyone does. If they did, they would erect a boxing laboratory designed to manufacture more extraordinary champions like him.

But let’s say, hypothetically, we could do that. What would that lab look like? First off, the (mad) scientist would be someone like Anatoly Lomachenko, Vasyl’s father, who had plans to create a generational talent before his son was even conceived. He placed the first pair of boxing mitts over Vasyl’s tiny fists when he was just three days out of the womb. He oversaw Vasyl over the entirety of the winningest career in amateur boxing and remains intimately involved in his professional training. When Vasyl is sparring, he personally counts the punches in each round, relentlessly tracking it, looking for patterns. In one of those “inside the training camp” videos, Vasyl explains, in halting English, that he is like a video game and his father is the gamer. One of his nicknames is “The Matrix.” So that’s your foundation, his reason, if you will. But knowing the designer doesn’t bring us much closer to understanding how one creates such an athlete—an athlete whose feats draw references to stunts that are impossible outside the confines of a simulation. We know the basics of his training—the marathon-length runs; the bag, ball, and pad work; the sparring—all of it executed with a single-mindedness that points to something embedded in his DNA. But even this doesn’t really explain what makes his performances different. This warrants a brief interlude to explain what I mean by “different.” There are two aspects of Lomachenko’s game that are unparalleled, I would argue, in the history of the sport. The first and most obvious to a casual observer are his combinations. He assembles sequences of head movements and punches which make his opponent’s attacks appear choreographed to miss, and his own, in equal and opposite measure, entirely confounding in their precision. Simply put, whoever he is fighting has no idea where the punches are coming from, but from an observer’s perspective, they look like they’re coming from exactly where they need to. There’s an elegance to it, like puzzle pieces fitting together. Norman Mailer once wrote that a knockout results from a failure of communication between mind and body. “A pugilist with an authentic desire to win cannot be knocked out if he sees the punch coming,” he writes. “In contrast a five-punch combination in which every shot lands is certain to stampede any opponent into unconsciousness.” Lomachencko does this better than any other fighter today. And, more importantly, when he isn’t able to “stampede” said opponent into a coma, his offence is often so overwhelming, so demoralizing that world-class boxers—some of them champions—have simply quit mid-match. Teddy Atlas, a former trainer to Mike Tyson and one of the most experienced voices in the sport, has an ominous way of describing this ability: “He takes men’s souls.” The second part of Lomachenko’s game is, in large part, what makes the first possible and that is his footwork. It is balletic. Last December, Lomachenko fought Guillermo Rigondeaux, a matchup that was the stuff of boxing purists’ wet dreams. Rigondeaux is another one of history’s winningest amateurs and he had a near-perfect record over something like 500 fights before he was walloped by the Ukrainian. After the fight, writer Hamilton Nolan observed that Lomachenko "can be anywhere in a 270-degree radius of your face before you can move to meet him…(Standing in front of you) he slips punches with the ease of a grown man pretend-boxing with a toddler. You can’t find him, and if you do you can’t hit him, and the whole time he’s hitting you.” To explain these more particular talents you’d have to investigate the unorthodox aspects of Lomachenko’s training. Anatoly did not allow Vasyl to begin training as a boxer until he took up traditional Ukrainian dance. One of his favourite training implements is the agility ladder, and he regularly wears out his shoes using it. On film, his warm-ups sometimes include these knuckle-to-palm handstand hops, which seem more like something an acrobat would do to open his circus act than what you’d see from a boxer. On his rest days he swims, juggles, and plays tennis (occasionally against himself). At the end of full training days, he does at least 30 minutes of mind flexibility exercises, brain teasers, and reflex drills, all part of a program crafted by a designated psychological trainer who is a permanent fixture in his camps. Then there are the breathing exercises, remarkable both in their simplicity (holding his breath for as long as he can) and sophistication (he uses computerized breathing apparatus to measure the force of his in/exhalations). Sports psychologists, fight trainers, armchair critics, and awestruck magazine writers have twisted themselves into knots trying to connect the dots between his preparation and performance. How exactly does “x” allow him to do “y”? Maybe you’re only reading this because you were hoping to glean a few training tips, which, with enough sticktoitiveness might lead to a few flashes of athletic brilliance. If that’s the case, I’m sorry to tell you that much of what this boxer is able to do simply defies explanation. It could be, for anyone else, that spending hours doing brain teasers will do very little to improve one’s boxing IQ. It could be, for anyone else, that learning to juggle will do nothing to help you land a cleaner punch or avoid one. The consensus among the boxing cognoscenti is that what Lomachenko can do doesn’t totally make sense. The BBC’s Mike Costello described it as “almost sorcery.” If one were forced to explain the formula to Lomachenko’s success, say in a contrived think piece, it would probably sound something like this: two generations of irrepressible devotion to the sport, an arsenal of physical and psychological gifts, and a healthy pinch of creativity. But the secret, I think, is his tacit recognition that there’s more to it than that. History always demands more. Originally published by GLORY. Considering a blossoming source of stupidity in our current cultural moment One of my all-time favourite pieces of political magazine writing was Wells Tower’s 2012 profile of Mitt Romney. As some well-to-do magazines have sometimes done, GQ paid for the fiction writer and occasional correspondent to join the other political journalists on the campaign bus. The idea was to get a novelist’s eye on Romney.

Of course, anybody who had any interest in reading a piece like this probably already had a basic idea of what Romney was like: Your cookie cutter millionaire politician, famously boring, known as much for being out-of-touch with the average American as he was for his attempts to disguise how out-of-touch he was.[1] But it was precisely this fact—that Romney was almost the perfect cardboard cutout of a politician—that gave Tower an opening to write what turned out to be a revealing character examination. There was something to unveil, and it was right there in all his campaign blubbering. “Mitt Romney once said that he cannot imagine anything worse than polygamy,” Tower wrote of Romney’s a-little-too-enthusiastic attempts to dispel concerns about his Mormon background. “This is a failure of the imagination. I can in a split second imagine many things worse than polyamory. One, two, three, go! The Holocaust, guzzling a bucket of pus, a baboon fucking a human baby.” Granted, Tower did not have had to dig very deep to figure out what was going on beneath the surface but watching him scratch at it was fun, edifying even.[2] He humanized Romney, overcoming near-heroic efforts on the politician’s part to avoid even trace amounts of humanity. He was able to write something interesting not in spite of the fact that Romney is boring, but because of it. This is what writers are supposed to do: To find the human inside the robot, or the monster inside the slick and steady operator. But things have changed now. The monsters are no longer hiding. * Here are the most important things that future generations will need to know about Donald Trump.

Now, if you cannot accept these premises, by all means, go back to whatever activities otherwise occupy your time (throwing eggs at the town newspaper boy?). It wouldn’t be fair to ask you to care about the role of writers in our current cultural moment because if you still believe Donald Trump is a good president with all that we now know about him, you must believe it’s the writers—or the journalists, or the people with a functioning sense of decency—who have not been telling the truth. If you don’t trust them, there’s no reason to think you’ll trust me.[3] If you’re still here, here’s my thesis: Mr. Trump, and the broader phenomenon of which he is a part, has made us dumber. This is not because Mr. Trump is dumb (which he is) or because the people who elected him are stupid (which, I would bet, most of them are) but because he defies the ordinary conventions of trying to conceal one’s stupidity, self-interest, etc. The parts of our brain that evaluate the most powerful people in the world are atrophying because we no longer have to do the basic work of trying to figure out who these people are. Consider our comedians. Most have said this president is very bad for comedy. Bad, they say, because it’s nearly impossible to match the absurdity of what’s happening in real life in a way that would register as a joke in the human brain.[4] Take Stephen Colbert. Colbert went from playing a very smart and funny caricature of a right-wing blowhard in the Bush years to something significantly less funny when he took over from Letterman. Granted it’s a totally different show, but it’s also the only kind he could do today. Now he just plays himself, matter-of-factly pointing out all the terrible or stupid things Trump has done day after day, barely even making jokes about it. Because, you see, the things Trump is doing are the jokes. A solid—I don’t know—93% of Colbert’s bits stop probably two sentences shy of outright saying “look how dumb this is.” The success of any joke depends saying something interesting and not immediately obvious as a way of saying something true. Trump resists any effort to do that. The funniest bit I’ve seen Colbert do since he started doing the Late Show was one about the flame-out candidates in the 2016 democratic primaries and the only reason it was funny was because he had to do more work to make fun of these people. There was still room for him to say something more creatively absurd than what was going on in real life. Point is, you got to do the work. Being well-informed (or funny) requires some degree of effort. It means caring about things that are not as bombastic or salacious as any one of the dozens of scandals that have happened under Mr. Trump’s tenure. Usually it requires patience and a degree of nuanced thought to wrap one’s head around. Mr. Trump, and by extension, our efforts to accurately portray him, are to nuanced thinking what a rancid fart is to a wine tasting—unpleasant, uninteresting, and masking what you should be paying attention to. * There are fucked up things that happen in every government. In fact you could probably even make a compelling case that many other governments were far more fucked up, if for no other reason than the fact that their actions were always handled and spun more effectively—chewed by a bureaucratic machine to be easier to swallow. That’s what politicians do. It is not an accident that so many people are willing to shrug off tens or even hundreds of thousands of deaths in every war because those people are not “our people.” But those politicians and their policies invited scrutiny. Politicians invite scrutiny by virtue of existing, because existing as a politician means embodying two conflicting ideas: one, that you must accurately represent a group of complex, flawed and often very different people (i.e. you are one of them), and two, that you can be—at least implicitly—better than them. Then you have to convince them you can be both at the same time. I don’t believe you can do this with any level of sincerity, which is why sincerity is not something we associate with politicians. It is why we have a sort of duty as citizens to pay such close attention to them. It is why “norms” exist. They allow us to pare away distractions that might interfere with the activity of paying attention to things that matter. They are also what make politics boring. Donald Trump blew all that up. Despite his many (many) lies, he is nothing if not sincere. Although it’s a kind of emotional sincerity, in which he’s sincere about being self-interested, greedy, etc. He embraced this role as the country’s id, and in doing so gave the people who endorsed him permission to do the same. Journalists, writers, and people otherwise trying to figure out the magnitude of this noxious plume of idiocy, can’t really, because they’re in it. How are you supposed to evaluate the moral implications of the leader of the free world dismissing predominantly black countries as “shitholes” when literally within a week, you find out he paid out $130,000 during his campaign to cover up an old affair with a pornstar, an affair that he knew could influence the outcome of the election, and did so in ways that we now know were not totally above-board? I’m not here to write another story pointing out this stuff. God knows you’ve heard enough about it. What I’m more interested in is how he’s managed to rob us of the basic ability to even think about whether any of this stuff matters; whether it has legitimate bearing on his position, or the decisions he makes. Because the answer to that question is already both completely obvious and completely different depending on who you are. He invites ridicule or defensiveness, but makes more traditional kinds of scrutiny very difficult. But, what would that even look like? He’s a piece of shit and also the president, so his piece-of-shitness is a near-daily assault on our senses. The guy is a walking billboard of every shameless excess and vice on which American stereotypes are built. And we still entertain ideas that maybe he is more complicated than that. Do you think Donald Trump has an inner life? Do you think Donald Trump believes anything? Do you think there are complex human forces of love or anything like it at work in Donald Trump’s life? No. There is nothing to Donald Trump except all that you already see on TV. And yet the standard political conventions (read: “norms”) haven’t adjusted to a person like this, and so basically half of the political machine in the U.S.—politicians, pundits and others who inform far too many people in the country—end up spending full days thinking of why all the things you see on TV or read about him are wrong, or don’t matter. Trump is the best at it, of course, but him defending himself from the (*grand waving gesture indicating everyone who has ever said anything bad about him*) fake news, well, that comes from a different place, somewhere more primal, like an animal trying to stay alive. David Roth, the Thompson to Trump’s Nixon, called him “the president of blank sucking nullity.” “The most significant thing to know about Donald Trump’s politics or process, his beliefs or his calculations, is that he is an asshole; the only salient factor in any decision he makes is that he absolutely does not care about the interests of the parties involved except as they reflect upon him. Start with this, and you already know a lot. Start with this, and you already know that there are no real answers to any of these questions.” Which is I guess comforting, but also sad. Once you manage to get a clear-eyed look at things, I think you’ll realize there’s nothing to see. It’s just emptiness all the way down. --- Notes: [1] You remember when Romney said his favourite meat was “hot dog” at a campaign dinner? “And, everyone says, oh, don’t you prefer steak? It’s like, I know steaks are great, but I like hot dog best, and I like hamburger next best,” said the man with a net worth of $250 million. [2] Pus-guzzling jokes and all. [3] I know this sort of talk opens me up to the familiar criticisms around elitism. I understand there are many people who love Donald Trump and give him (largely undeserved) credit for many things that have a far more direct and powerful impact on their lives than the latest scandal du jour. Say I’m a coal miner who still has a job and who hears Trump talking about saving my job all the time, I wouldn’t want to listen to some ivory tower egghead in some liberal cosmopolitan enclave (or whatever cartoonish idea I have about journalists) try to tell me why this guy who (I think) saved my job is actually bad because of some bad thing he’s done that doesn’t affect me, and then listen to these same people tell me I’m wrong not to care about it. I get that. The problem with this is that it a) assumes that there aren’t writers/journalists significantly closer to home (in both geography and attitude) who aren’t trying to uncover truths that do affect me, the coal miner; and b) suggests that the word of a single proven pathological liar is worth more than that of large professional groups whose very existence depends on delivering the truth accurately. If you don’t agree, consider the consequences for individual journalists and their organizations when they get something wrong vs. the consequences (read: lack thereof) for Donald Trump. [4] Patton Oswalt actually has a joke about this in which Mr. Trump is a demented homeless man who shits on the street, and before the comedian is able to tell a joke about his shitting on the street, Mr. Trump is already wearing his own fecal matter as a sombrero. |

Past Essays |